In these faux-buddhist times, it’s become a true cultural meme: “Live in the present!”

It’s the fault of the beats, really, Kerouac especially, giving a Zen paint job to all the self-indulgent behavior they could muster, which was substantial. Now we get Zen home decorating, Zen cuisine, Zen motorcycling, for Christ’s sake. But the worst of all of it is the live-in-the-present motif, which seems to be interpreted, as often as not, as licence to reject responsibility. You can’t fault Zen itself, which is in reality all about accepting responsibility. Far from the hedonism spawned by everyone living “in the moment,” Zen actually teaches that desire, which motivates all this extremity, is something that we could all do without.

But let’s look at the idea of living in the present itself. Can such a thing be done?

Not a chance. First of all, from a purely physical point of view, it’s impossible, because by the time any information reaches our senses, it is already in the past, and from there it still takes time for us to process that information and become conscious of it. It may only be microseconds, but it’s not the present.

But maybe we’re talking about the present as it relates to sense data already processed, and ready for use. In this case, it doesn’t matter that the events themselves are in the past; the present we’re talking about refers to the interior present. Can’t we live in that?

Good luck. Suppose some light reflected from a moving bus enters your eyes and is processed. Just to identify that light pattern as a bus requires you to use information stored in your memory from a lifetime of observation. You’re stuck in the past. Not only that, but if the bus happens to be moving toward you, you had better be thinking of the future, or you soon won’t have any.

You could say this is pointless quibbling, that what is meant by the present in this case includes events and decisions in the immediate temporal vicinity. Also, you get to take advantage of all you have learned in your life in interpreting the present. And, of course, you get to consider the immediate future. Enough to stay alive, at least. Okay, enough to have a reasonably secure life.

Trouble is, when you start expanding the bubble around the present to include what you need for survival, you immediately run into problems with what that means. In the end, for most people, that seems to involve cars, cell phones, huge televisions, and the sources of money to pay for all that. Next thing you know, living in the moment just means doing what you want, and to hell with the consequences, for yourself, yes, but more often the consequences for others.

Blap! Just like that, you’ve taken a concept out of Zen and turned it completely around to mean its opposite.

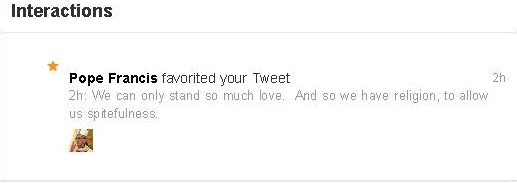

This sort of thing is not unusual where religion is concerned. Lots of airy contemplation and metaphysical nuance at the top, but by the time you get down to the ground zero believer, it’s boiled down to a list of rules and regulations. We are, of course, familiar with this for the Abrahamic religions. God knows that what the nuns taught us at St. Philip Neri School all those years ago had little to do with the rarified theology debated at Notre Dame and the corridors of the Vatican. But with Buddhism, somehow, we all think we get it.

I don’t consider myself a Buddhist; I don’t believe in any religion, actually. I was enchanted by it for a time in my youth, however. I read all of the Western Zen writers, like Alan Watts, and moved on to the works of D. T. Suzuki and what other Japanese writers I could find in translation. This sparked an interest in Buddhism in general, and so I was delighted when I met a young man from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), who was an ardent Theravada Buddhist. Theravada is the closest thing in Buddhism to orthodoxy, so I jumped at the chance to get at the roots of it all. My friend was delighted in my interest in his religion, and gave me a handful of books and pamphlets. To my dismay, what I found was the same old list of things to do and things not to do. It could easily have passed for my old grade school catechism with a few minor changes in terminology.

What happened to all that cool Zen stuff about letting go and being in the moment? I later learned that, even in Zen, the practice of it was far different from the lofty metaphysics, involving more sitting in wretched discomfort (for someone raised to sit in chairs), and getting whacked with a stick than any of that marvy freedom I’d been reading about. My horrible nuns, it seems, had been Zen masters all along!

By the time any religion percolates down to the great unwashed (us), it’s all about rules and regulations, sprinkled with more or less of magical ritual. I think of the St. Christopher statues in the cars of my youth, or the prayers rated with the precise number of days off from Purgatory their recitation would get you, or how, if you took communion on nine consecutive first Fridays of the month, you were guaranteed salvation. Interesting that I never made it past five!

Buddhism is no different. Think of the prayer flags of Tibet, or the redemptive power of reciting “Namu Amida Butsu” over and over in the Japanese Pure Land school of Buddhism.

I must say we’ve been pretty clever in our cooption of Buddhism in Western culture, though. We’ve taken some of the lofty metaphysics of a religion we’ve no intention of following seriously, stripped it of any inconveniences, reinterpreted it to suit ourselves, and imagine ourselves to be marvelously spiritual.

Sweet!